Burnside groups for the masses

Preliminaries

The most impressive-sounding class I have ever taken is Abstract Algebra. Dropping that title always made me sound like a genius.

But abstract algebra is not nearly as technical as it sounds — I certainly don’t think I’m a genius! All it does is abstract the process of solving for \(x\) into new yet familiar structures. Here’s an example. Say I give you a list of numbers (or letters, or Viking runes; it really doesn’t matter) that can be “multiplied” together. For the sake of concreteness, I’ll give you two, which we call \(a\) and \(b\). We can multiply them together in any order and use exponential notation in the obvious way; for example, \( a^3=a*a*a \). Our algebraic system is subject to only one rule: raising either \(a\) or \(b\) to some particular integer, call it \(n\), equals an identity element \(e\) that we can think of as representing \( 1 \); it can be eliminated from any product. Then, say, \(a^{n+1}=a\) because we can also write \( a^{n+1} = a^n * a^1 = e *a \).

Say we have \(n=5\) so that \( a^5=e \) and \( b^5=e \) always holds. Here are some elements of our strange new algebraic system:

\[ a^2 , b^3 , ab^4 , b^4 a, aba^3 ba^2 b \]

Note that, when I said the only rule, I really meant it. Commutativity doesn’t even hold, which is why I could list \( ab^4 \) and \( b^4 a \) as distinct.

How many distinct elements does our algebraic system have? More generally, does it have a finite or infinite number of elements?

Table the previous two questions for a moment. I’m already tired of the cumbersome term “our algebraic system”, so I’ll give up the ghost. Such a system where we start with \(m\) distinct letters in which any term raised to the \(n\)th power is the identity is called the free Burnside group of rank \(m\) and exponent \(n\), or \(B(m,n)\) for short. The one I introduced was \( B(2,5) \).

The first Burnside problem asked whether all such \(B(m,n)\) are finite. Intuitively, or at least according to my intuition, the answer ought to be yes, but the Russian mathematicians Evgeny Golod and Igor Shafarevich proved in 1964 that some \(B(m,n)\) are infinite. The second Burnside problem asks the obvious followup: which \(B(m,n)\) are infinite?

I asked to table those two questions from earlier because I don’t actually know the answer. Nobody does, actually! It is as of yet unknown how many elements \(B(2,5)\) has.

Of course, just because the second Burnside problem is unsolved doesn’t mean I’m done talking about it. I’m going to give a brief, somewhat loose with details introduction to abstract algebra and category theory and explain how they relate to Burnside groups. My hope is that anyone can understand this blog post no matter their background in mathematics, so I rely on intuitive arguments. If you ever want a more thorough explanation, though, follow the links to Wikipedia. I don’t know who all these math PhDs are that write Wikipedia articles about the Yoneda lemma, but I for one am very grateful to them.

Group Theory

\( B(m,n) \) is an instance of a group, one of the fundamental algebraic structures in mathematics. Groups are defined through a set \(G\) and a binary operation \(*\) (“binary” just means you apply it to two things and get one thing, like addition or multiplication) on that set that obeys the following three1 axioms:

- \(*\) is associative. If we chain together elements for something like \( x * y * z \), we can evaluate either \( x * y \) or \( y * z \) first and still get the same answer.

- There exists some element \( e \) in \( G \) that acts as an identity under the operation. For any other \( x \) in \( G \), \( e*x=x*e=x \).

- Given some element \( x \) in \( G \), we can find an inverse \( x^{-1} \) such that \( x * x^{-1} =x^{-1} * x=e \).

The axioms are not very demanding, so it’s easy to come up with examples of groups – say, the integers \( \mathbb{Z} \) under addition or the nonzero complex numbers \( \mathbb{C} \setminus \{0\} \) under multiplication. The axioms are also powerful enough to derive a few useful algebraic properties:

- The identity is unique – if there is some other element \(e’\) in the group satisfying the same property as the regular identity \( e \), we must have \(e=e’\). \(e * e’ = e’ \) because \( e \) is an identity, but also \( e * e’ = e \) since \( e’ \) is an identity too, so \(e=e’\) by transitivity.

- We can cancel elements – given that \( x * y = x * z \), we can always conclude that \( y = z \). Cancellation holds because we can multiply both sides of the equality by \( x^{-1} \) for \( x^{-1} * x * y = x^{-1} * x * z \), but then \( e * y = e * z \) and \( y=z \).

- Inverses are unique like the identity. Say \( x \) has two inverses \( x^{-1} \) and \( x^{-1\prime} \). Then \( x * x^{-1} = x * x^{-1\prime} \) and \( x^{-1} = x^{-1\prime}\) by cancellation.

Both examples of groups I gave earlier were obviously infinite, but it’s easy to come up with finite groups too. One kind of stupid example is the trivial group with a single element where the operation always gives back that single element. It turns out this satisfies all the axioms! The trivial group will be useful later. I write it as \( \{ * \} \).

One “better” example is the set of all nonnegative integers less than \(6\). Define an operation called addition modulo 6 as follows: add two integers together and, if the result is greater than 6, subtract 6 from it until we have an integer that is less than 6.2 Then \(2+2=4\) as usual, but \(5+5=10-6=4\). Such a group is called \( \mathbb{Z}_6 \). In fact, we can define a group \( \mathbb{Z}_n \) for any positive integer \(n\). I denote addition modulo \( n\) as \(+_n\); I could just use a normal \(+\) every time, but strictly speaking, it’s a different operation in any \( \mathbb{Z}_n \).

Of course, we don’t just care about groups as isolated entities. We also want to define something analogous to functions between groups. Notice that I said something analogous to functions and not functions. We normally think of functions as operating between sets, in which case no operation is involved. A function between sets has to be well-defined with respect to elements, so that we don’t simultaneously have \( f(1)=1 \) and \( f(1)=2 \). A “function” between groups has to be well-defined with respect to elements and operations. But what does it mean to be well-defined with respect to operations?

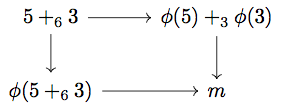

I could give the condition immediately, but I find the long way illuminating. Say we have a set-function \(\phi\) from nonnegative integers less than 6 to nonnegative integers less than 3. We want to see if it could also be a sort of function between the groups \( \mathbb{Z}_6 \) and \( \mathbb{Z}_3 \). Consider the element 2 of \( \mathbb{Z}_6 \). As far as \( \mathbb{Z}_6 \) goes, \( 2=5+_6 3 \). \(5+_6 3\) is another way of saying \(2\), so we could evaluate the expression \(5+_6 3\) first and then apply \(\phi\) to it for \(\phi(5+_6 3)\). \(5\) and \(3\) are bona fide elements of \( \mathbb{Z}_6 \) on their own, though, so we could proceed in the opposite order, applying \(\phi\) to each element first and then adding them in \( \mathbb{Z}_3\). Then we would have \(\phi(2)+_3 \phi(3)\). It really helps to draw a diagram:

We have two ways of getting to an element \( m \) of \( \mathbb{Z}_3 \), depending on whether we start with the operation or with the set-function. Well-definedness means we should be able to follow the arrows in any way in the above diagram and get the same value for \(m\) — the diagram should commute. In other words, we should have \(\phi(2+3)=\phi(2)+\phi(3)\).

The above logic is easily generalized. For a function \( \phi \) operating on the underlying sets of the groups \( G \) and \( H \), respectively having operations \( * \) and \( \bullet \), \( \phi \) “preserves the operation” if the following equality holds for arbitrary elements \(x\) and \(y\) in \(G\):

\[ \phi(x* y)=\phi(x)\bullet \phi(y) \]

Any mapping between groups obeying the above property is the group equivalent of a function – a homomorphism.

For any two groups \( G \) and \( H \), the existence of a homomorphism \( \phi \) from \( G \) to \( H \) suggests that the groups have similar structures. \( H \) could have substantially fewer elements than \( G \), but its operation acts in a similar way. Have you ever heard about how mathematicians can’t distinguish between a coffee cup and a donut? The “joke” is that coffee cups and donuts are topologically identical. Even though a coffee cup has a more “complicated” shape than a donut, they are both lumps of matter with a hole. We could continuously deform a coffee cup into a donut without breaking or tearing anything. \( G \) and \( H \) have the same relationship. We can deform \(G\) into \(H\), losing detail but not breaking or tearing. If we want to to emphasize the relationship instead of the mapping, we can say \( H \) is a homomorphic image of \( G \).

(Well, strictly speaking, it’s possible that not all of \( H \) is “captured” by \(\phi\). We could even have that \(\phi\) sends everything to the identity element of \(H\) and the homomorphism condition would still be satisfied. I’m being loose with details, just like I said!)

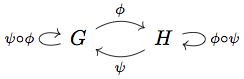

By applying \( \phi \) to \( G \), we preserve structure but often lose detail. Not always, though. It is possible that there is also a homomorphism \( \psi \) from \( H \) to \( G \), and that we can follow the two homomorphisms in sequence and end up in the same place; that is, \( \psi(\pi(G)) = G \). Have another diagram:

The diagram suggests going from \( G \) to \( H \) does not involve any “loss of information”. Once we get to \( H \), even though we forgot everything about \( G \), \( H \) has enough going on to faithfully reconstruct \(G\). We say in such cases that \( \phi \) and \( \psi \) are isomorphisms, or that \( G \) and \( H \) are isomorphic. But how similar do \( G \) and \( H \) have to be? In a sense, they have to be the same group! Think of \( G \) and \( H \) as being two representations of the same thing, like \( 1 +1 \) and \( 2 \). Isomorphisms actually maintain every property of groups besides irrelevant ones like whether the elements are letters or numbers. The symbol \(\cong\) denotes isomorphism, so that we could write \(G\cong H\) in the above example.

It is actually more common to define an isomorphism between groups as a homomorphism that is also a bijection. I prefer the definition I gave, though, and not just because the reader may not be familiar with bijections. The definition I gave emphasizes the idea of groups as sets with “extra information”. Moreover, it also works to define isomorphisms between mathematical structures other than groups, as we will see very soon.

In abstract algebra, it is almost always correct to think of isomorphism as equality. It is extremely common, for instance, to say that an algebraic structure is unique up to isomorphism. Then, if we come up with two objects satisfying the requirements, they must be isomorphic.

Believe it or not, the above introduction to group theory is not yet abstract enough! We now know what a group is, and can think about Burnside groups on a higher level, yet describing an arbitrary \( B(m,n) \) is still out of our grasp. We need “abstract abstract algebra”, better known as category theory.

Category Theory

Categories are a little trickier than groups to define, but not by much. A category \( \mathscr{C} \) (the fancy script is of utmost importance) has two “kinds of things” in it:

- A set of objects denoted \( \mathrm{Obj}(\mathscr{C}) \).

- For any two objects \( A \) and \( B \) in \( \mathrm{Obj}(\mathscr{C}) \), a set of morphisms denoted \( \mathrm{Hom}_\mathscr{C}(A,B) \). We say that a morphism in \( \mathrm{Hom}_\mathscr{C}(A,B) \) has \( A \) as its domain and \( B \) as its codomain.

Like any good mathematician, I will now start abusing notation. I will write morphisms as, say, \( f : A \to B \). That means \( f \) has domain \( A \) and codomain \( B \), but such notation does not specify which category we are working in. It will always be evident from context, though.

The easiest example of a category is probably the category of sets, which I will denote \( \mathcal{Set} \). Any set you can think of is an object in \( \mathcal{Set} \). The morphisms of \( \mathcal{Set} \) are, of course, ordinary functions.

Like groups, categories must obey certain axioms:

- Composition of morphisms is defined. For some morphism \( f : A \to B \) and \( g : B \to C \), we have another morphism \( f \circ g : A \to C \).

- Composition of morphisms is also associative such that, for \( f : A \to B \), \( g : B \to C \) and \( h : C \to D \), we can evaluate the expression \( f \circ g \circ h \) in any order and get the same morphism in the end.

- For any object \( A \), there is an identity morphism \( \iota_A : A \to A \). \( \iota_A \) has to actually be an identity, so that for \( f : A \to B \), we have \( \iota_A \circ f = f \circ \iota_B = f\).

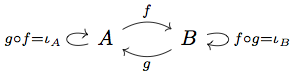

We’re getting into abstract nonsense territory, so have a diagram of a simple category:

This is exactly the same as the isomorphisms diagram in the last section, but with the objects and morphisms renamed for the sake of generality. Notice that both objects have identity morphisms and every possible composition of morphisms yields a morphism that’s already there.

Diagrams (or drawings, I should say; a categorical diagram means something rather specific) are everywhere in category theory. As words, categorical concepts are often confusing, but drawing a categorical concept often makes it substantially clearer.

Does \( \mathcal{Set} \) obey the category axioms? Yes, because otherwise I would not have given it as an example of a category. Non-tautologically, every set has an identity function from itself to itself. Also, if we compose two functions between sets, we have another function between two sets of the correct “domain” and “codomain”. Finally, composition of set functions is indeed associative.

You are hopefully unsurprised that there is a category of groups, denoted \( \mathcal{Grp} \). As with \( \mathcal{Set} \), any group you can possibly imagine is in \( \mathcal{Grp} \). The morphisms of \( \mathcal{Grp} \), though, are homomorphisms as defined in the previous section. It turns out that the composition of two homomorphisms is always another homomorphism, every group is a homomorphic image of itself and homomorphism composition is associative, so \( \mathcal{Grp} \) really does satisfy the axioms for categories.

Category theory is useful because it allows us to see the similarities in how mathematical objects relate to each other. The notion of an isomorphism is easily generalized to an arbitrary category. An isomorphism of \( \mathscr{C} \) is just some morphism \( f : A \to B \) such that there is another morphism \( g : B \to A \) and \( f \circ g = \iota_A \) — that is, \( f \) and \( g \) compose into an identity morphism. I already defined isomorphisms in \( \mathcal{Grp} \), but what about \( \mathcal{Set} \)? The isomorphisms of \( \mathcal{Set} \) are just the (bijective) functions between sets with the same number of elements. It might seem wrong that the sets \( \{1,2,3\} \) and \( \{math, German, economics\} \) are considered isomorphic in \( \mathcal{Set} \), but it just comes down to the fact that \( \mathcal{Set} \) doesn’t have much “going on”. An element of a set doesn’t “do anything” except be an element, so morphisms in the category \( \mathcal{Set} \) don’t give a rip what any given element fundamentally is.

Two very important definitions in category theory for a category \( \mathscr{C} \) are:

- The initial object is that object \( A \) such that, for any object \( B \) of \( \mathrm{Obj}(\mathscr{C}) \), there is one and only one morphism \( f : A \to B \).

- The terminal object is that object \( A \) such that, for any object \( B \) of \( \mathrm{Obj}(\mathscr{C}) \), there is one and only one morphism \( f : B \to A \).

I called these two concepts, but they are in a sense just one. Given any category \( \mathscr{C} \), we can always reverse all the arrows (that is, swap the domain and codomain of each morphism) and we get the “opposite category”, denoted \( \mathscr{C}^{op} \). Obviously, an initial object in \( \mathscr{C} \) is a terminal object in \( \mathscr{C}^{op} \), and vice versa. The concepts of initial and terminal objects are therefore said to be dual. I will sometimes refer to only initial objects for the sake of convenience, but worry not! Everything I say will also be true for terminal objects if you reverse all the arrows.

Take a moment to consider the initial and terminal objects of \( \mathcal{Set} \). In \( \mathcal{Set} \), the initial object is a set \( S \) such that, for any other set \( T \), there is only one set-function \( f : S \to T \). Such a set does exist: the empty set \( \varnothing \). Since the empty set has no elements, we can only define a function \( f : \varnothing \to T \) by saying absolutely nothing about where each “element of \( \varnothing \)” is sent, and there’s only one way to say nothing. Dually, the terminal objects of \( \mathcal{Set} \) are any sets with just one element. If \( T \) has just one element, then given any other set \( S \), there is only one way to define a function \( f : S \to T \) — by mapping every element of \( S \) to the single element of \( T \).

So then \( \mathcal{Set} \) has just one initial object, but infinitely many terminal objects, because there are infinitely many single-element sets. Why, then, did I refer to the terminal object? My justification is that any two initial or terminal objects of a category are isomorphic. That holds no matter what category we are operating in, and no matter what isomorphism means in our category.

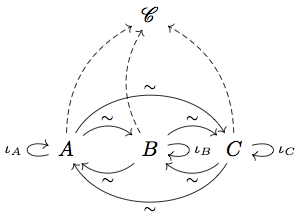

If you don’t believe me, try drawing a category yourself and make multiple objects initial:

The above is a category with three initial objects, \( A \), \( B \) and \( C \). The \( \mathscr{C} \) is just the rest of the category. For every ordered pair \( A \), \( B \) and \( C \), we have only one arrow with that domain and codomain. Then we can compose — say — the unique morphisms from \( A \) to \( B \) and \( B \) to \( A \); if they compose to form \( \iota_A \), we have that \( A \) and \( B \) are isomorphic. Is this the case? Yes, because \( A \) is only allowed to have one arrow to itself as an initial object, and it has to be \( \iota_A \)! By the way, we can draw a little \(\sim\) above an arrow to say that it represents an isomorphism. Category theory proofs usually work this way — we draw some objects and arrows and notice that something is forced by definitions.

I called category theory “abstract abstract algebra” earlier. Consider the informal proof above that initial objects are isomorphic. We have one layer of abstraction by saying that \( A \), \( B \) and \( C \) are the same “kind of thing”. We have another layer of abstraction because we aren’t specifying what “kind of thing” \(A\), \(B\) and \(C\) are — they could be sets, groups or even more categories3! All this abstraction is tricky to intuitively grasp, but it allows us to reach breathtakingly general mathematical conclusions, as we’ll learn in the next section.

By the way, “abstract abstract abstract algebra” or any “abstract\(^n\) algebra” is also category theory. It’s categories all the way down!

As a hopefully interesting aside, initial and terminal objects overlap entirely within \( \mathcal{Grp} \). Given any object \( G \) of \( \mathcal{Grp} \) — that is, any group \( G \) — there is only one homomorphism \( \phi : G \to \{*\} \), sending each element of G to the single element of \( \{*\} \). There is also only one homomorphism \( \phi : \{*\} \to G \), sending the one element of \( \{*\} \) to the identity of \( G \). Then the trivial group (or a trivial group, we should perhaps say, but they are all isomorphic anyway) is an initial and terminal object, a zero object, as they are sometimes called.

The existence of zero objects in a category implies something rather interesting — that we can find a morphism between any two arbitrary objects. That property fails in \( \mathcal{Set} \), where there never exists a morphism \( f : A \to \varnothing \) for nonempty \( A \). Otherwise \( f \) would need to map some element of \( A \) to an element of \( \varnothing \), which has no elements! In \( \mathcal{Grp} \), though, given objects \( G \) and \( H \), there are trivial homomorphisms \( f : G \to \{*\} \) and \( g : \{*\} \to H \). We can compose them for a homomorphism \( f \circ h : G \to H \). \( f \) is supremely uninteresting, mapping every element of \( G \) to the identity of \( H \), but it is worth noting that it always exists.

Remember that isomorphism often works just like equality. Defining a category and then finding its initial objects is then an excellent way of finding some mathematical entity that does the best job of fulfilling some goal. If the initial object exists, and if we can find it, then we will be done, because any other entity satisfying the goal is isomorphic. Such a construction is called a universal property.

By the way, if you enjoyed all this abstraction, I can’t recommend the inestimable Bartosz Milewski’s Category Theory for Programmers highly enough.

Universal Properties

It should be no surprise that there is a universal property defining the Burnside group \( B(m,n) \). The property is as follows:

B(m,n) is that group \(G\) generated with \(m\) distinct “letters” with the properties: (1) any letter operated on itself \(n\) times is the identity (2) for any other \(H\) obeying (1), there is a unique homomorphism \( \phi : G \to H \).

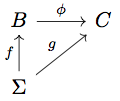

This is an oddly elliptical way of defining what is a fairly intuitive idea. I’ll try to convince you that it’s the best way of finding the Burnside group \( B(m,n) \). The universal property actually identifies the Burnside group as the initial object of a category; I’ll call this category \( \mathscr{B}_{m,n} \). The objects of \( \mathscr{B}_{m,n} \) are diagrams, or collections of objects and morphisms, that look like this:

Each object in \( \mathscr{B}_{m,n} \) is a candidate for the Burnside group \( B(m,n) \). The group itself is \( B \); we also have a set-function \( f \) identifying each “letter” in the “alphabet” \( \Sigma \) with an element of \( B \). We also have that every element of \( B \) raised to the \(n\)th power is the identity. Notice that the diagram itself is not a category; even though it has objects and morphisms, there are no identity morphisms and the objects are respectively a set and a group! We don’t need it to be itself a category, though.

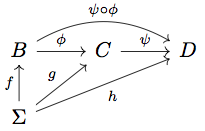

There is only one, admittedly not obvious, way to define morphisms in \( \mathscr{B}_{m,n} \):

There are two groups, \( B \) and \( C \) acting as candidates for \( B(m,n) \). Both of them draw from the same alphabet \( \Sigma \); there was no point in representing \( \Sigma \) twice, so the diagram is triangular. Moreover, there exists a homomorphism \( \phi \) between \( B \) and \( C \). Such a homomorphism does in fact exist due to both \( B \) and \( C \) obeying the \(n\)th powers condition; I hope you will forgive me for neglecting to prove this fact.

Oh, and the diagram needs to commute! That is, if we follow \(f\) and then \(\phi\), we need to get to “the same place” as if we had just followed \(g\).

We can, in fact, compose morphisms in \( \mathscr{B}_{m,n} \). The following diagram represents two morphisms of the category:

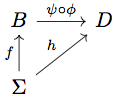

We can eliminate the middle and compose the homomorphisms \( \phi \) and \( \psi \):

where \( \psi \circ \phi \) is automatically another homomorphism.

It is hard for someone to hold all of these things in their head at the same time. However, if you manage to do so, you’ll see that the universal property from earlier is just asking for the initial object of the category \( \mathscr{B}_{m,n} \).

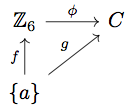

Just defining the universal property for a Burnside group \( B(m,n) \) is not enough to concretely describe \( B(m,n) \) in every case. It does, however, ensure that \( B(m,n) \) is unique up to isomorphism. One (relatively) easy case is the Burnside group \( B(1,6) \). I will show that \( B(1,6) \) is just \( \mathbb{Z}_6 \) as defined earlier.

The category \( \mathscr{B}_{1,6} \) has an alphabet of only one element, so \( \Sigma = \{ a \} \). An arbitrary morphism looks like this:

We need there to be only one such diagram for any two objects of our category: that, given the values of \(f(a)\) and \(g(a)\), there exists a unique homomorphism \(\phi\) making the diagram commute. Is this the case? Yes! The key is that the definition of \(\phi\) is forced by the commutativity of the diagram. We need \(\phi(f(a))=g(a)\). However, since both \(\mathbb{Z}_6 \) and \(C\) are candidates for \(B(1,6)\), we know that we can write any element in either as a power of \(f(a)\) or \(g(a)\). Say \(f(a)=1\) and \(g(a)=1\); we know that \(f(1)=1\) from the commutativity of the diagram. If we want to know where — say — \(3\) goes, we just write \(3=1+1+1\). Then \(\phi(3)=\phi(1+1+1)=\phi(1)+\phi(1)+\phi(1)=g(a)+g(a)+g(a)\). \(\phi\) is indeed a homomorphism, and there was no other possible way of defining it.

To be honest, the above paragraph isn’t quite a proof — it skips over too many details. That said, it provides the outline of an airtight proof that \( B(1,6) \cong \mathbb{Z}_6 \). If you wanted to identify some \( B(m,n) \) up to isomorphism, this is how you would do it.

Coda

The category-theoretical definition of \( B(m,n) \), when followed carefully, allows the mathemetician to avoid pitfalls. One Burnside group that has been “solved” is \( B(2,3) \), which has 27 elements. The number 27 was not at all obvious to me. I tried listing elements of \( B(2,3) \) and rapidly came up with more than 27 seemingly distinct elements.

“Seemingly” is the operative word in the previous sentence; I had listed (for instance) both \(aba\) and \( b^2 a^2 b^2 \), which are the same! Note that any element in \( B(2,3) \) operated on itself three times is the identity, so, for instance, \( (ab)^3 = ababab=e \). Then we have \( aba=b^{-1} a^{-1} b^{-1}\). But \(a^2 * a = a^3 = e \) and \(b^2 * b = b^3 = e \), so by the uniqueness of inverses, \( a^{-1} =a^2 \) and \( b^{-1} =b^2 \). It follows that \(aba=b^2 a^2 b^2 \), as claimed.

The word problem for groups deals with determining if two elements of a Burnside group \( B(m,n) \) are equal given their letter representations. (Actually, it’s a little bit more general than that, but that’s what it is for our purposes). It turns out that the word problem for groups is undecidable in general. We can prove equality and inequality on a case by case basis, but there is no algorithm answering the question for any such group. \( B(2,5) \), as it turns out, is one of the hard cases. Has category theory failed?

Obviously the answer is no, or I wouldn’t have written so much about it! The categorical definition of \(B(m,n)\) often makes Burnside groups seem more confusing than before, but it does at least establish that Burnside groups are well-defined — that there is some unique \(B(2,5)\) up to isomorphism, waiting to be discovered.

Is “discovered” the wrong word? I don’t think so. Math exists whether we think about it or not, which I find oddly comforting.

1 A purist might object that the group operation being closed and always giving another element of the group constitutes a fourth axiom. The way I see it, it’s impossible to define a function without giving its codomain, aka what kind of things it returns, so closure was specified by defining the operation. ↩

2 The fact that this procedure always results in a positive integer less than 6 (or whatever other nonzero integer we were using) is called Euclidean division. ↩

3 Technically, they would have to be \(small\) categories. We can’t talk about “the category of all categories”, because then we would be stuck forever thinking about whether or not the category of all categories contains itself. We can’t think about something for an infinitely long period of time until grad school. ↩